On December 7th, Pat Brandes was invited to speak at a breakfast meeting of a group called the Massachusetts Education Innovators. MEI is a collection of leaders from education non-profits, from city, district, and state offices of education, from unions, and from the legislature. The topic of the day was the role of “engaged funders” in accelerating innovation in education. Pat joined Paul Grogan, President of The Boston Foundation as featured presenters, then participated in a larger panel discussion with other Boston-area funders. Here’s what she said:

When Warren Buffet made his big gift to the Gates Foundation, he told the foundation staff that if they wanted to spur big change, they needed to fail fast and often. I think Barr would meet with Buffet’s approval on this score. Our history of grantmaking is littered with failures. Let me tell you about a whole portfolio of them.

For a long time, we had a strategy that we could fund great programs like many of those represented in this room, and that if and when they showed results, the district would adopt and scale them.

But it almost never worked like that – for a lot of reasons, including the fact districts aren’t always rational, however full they are of rational, smart, committed people. The forces of the status quo are powerful in bureaucracies and there are all manner of constraints. You hear it so often, it is cliché that there are no silver bullets in education, but that doesn’t stop us from falling in love with them, or from being heartbroken when the research calls them into question.

In November, for example, The Washington Post ran a story under the headline, “Research Does not Back up Key Ed Reforms.” It opened with these words: “There is no solid evidence supporting many of the positions on teachers and teacher evaluation taken by some school reformers today.”

Drawing on more than 40 studies or syntheses of research it debunked ideas like merit pay being linked in any meaningful way to student gains.

It points out that the now-in-vogue tool for gauging teacher effectiveness– “value-added assessments” – is not reliable or stable. And it calls into question the mantra that, if a kid gets a string of top-tier teachers in a row, it can erase the achievement gap. As it turns out, that’s never been proven.

I could go on – we all remember the small schools silver bullet and many others. But you get the point.

I think the good news is that we are all doing more research so that we’re learning what doesn’t work faster than we used to.

The bad news is that the pace of change is an outrage.

In my view we are in a crisis and for all the momentum the results are still not where they need to be. So maybe what we are missing is a deeper understanding of how change happens – particularly in complex, change-resistant systems like school districts. Districts are antiquated bureaucracies from the former century. They are highly political. With property taxes as their funding mechanism, they are also mired in structural racism.

So, it can be instructive to look at reform from the perspective of systems thinking. To do that I turn to Donella Meadows, who was trained by the great Jay Forrester, the father of systems thinking, at the technology school across the river. Before she died in February 2001, Meadows wrote a piece called “Leverage Points – Places to Intervene in a System”. It is a classic.

She starts by recognizing our very human longing for silver bullets and then lists 12 types of levers for changing complex systems. She ranks these levers based on their power to get big change in complex systems. It turns out we spend most of our time on the weakest ones – maybe because they are the easiest to move. This may be why the pace of change is slow.

The most powerful lever on Meadows’ list is to change the paradigm or mindset. For example – I think the public now believes that black and brown children can succeed in urban public schools. This has been a big paradigm shift – one that Boston’s charter schools deserve a big shout out for. They have changed the paradigm with high expectations for students and teachers. This is a huge lever for change!

Another critical mindset change that many of you are working on is that all urban children have the right to a good education, not just the children with parents who can get them into the better schools or who speak English as their native language.

This is why Boston’s District Charter Compact is so important – and why it is critical that we diversify who is recruited, enrolled, and retained in the charter schools. It is also why we must continue to shine a light on how ELL students are fairing.

Yet another paradigm shift is the one called personalized learning – it starts with the idea of multiple intelligences and travels all the way to sophisticated technologies for mass customization of learning. But the basic mind shift is that education is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor.

If you work on the lever of paradigm change – God bless you!

According to Meadows, the second most powerful lever is “setting the system goal” – articulating it repeatedly, standing up for it, and holding ourselves accountable to it. This one is critical for all of us and informs the rest of the conversation.

What are we after and how will we know we have gotten there?

Right now only 1.5 out of 10, BPS ninth graders go on to graduate from college – what should that number be? Three out of ten? That is the state average in Massachusetts – a state that arguably has the best education system in the nation.

Or is there a higher goal that defines a world class education?

Once we set the goals, do we also have ways to be transparent about progress? This is the work of core standards and testing and reporting on sub-groups and achievement gaps.

And this is the beauty of the Boston Opportunity Agenda – we have community goals for everything from school readiness to graduation rates. We have agreement at a high level on goals and we are tracking them publicly.

Setting the goals is such an important lever that I want to come back to it later in my remarks.

The third most powerful lever is “self-organizing” or “self-evolving.”

If schools and districts can’t innovate, they’re doomed. And “self-evolving” innovation is not innovation by smart outsiders executed top-down. It is an unleashing of the potential of kids, families, teachers and administrators.

This is why Michael Fullan argues that so many of the current reforms being proposed are destined to fail. They lean too heavily on limiting variability.

Looked at through this lens, the Bryk study of hundreds of Chicago elementary schools over 15 years makes sense. In schools that succeeded, Bryk found five common threads – four were about motivated individuals and groups:

- High quality professional capacity;

- Strong parent-community-school ties;

- A student-centered learning climate; and

- Leadership that drives change.

Empowered teachers. Empowered parents and communities. Empowered students. Empowered leaders. Organizing themselves around outcomes.

Bryk’s fifth element was “A coherent instructional system” which is an example of Meadow’s next lever (“Rules of the System”), but before I leave self-organizing, I want to point out one of the best recent examples we have in Boston – the Promise Initiative – a whole community in the Dudley area that is self-organizing to bring change for thousands of kids in a set of schools.

Let me stop here on the levers and take a few more minutes to talk about the goals because I think it is provocative for a group like this:

What really is our goal – significant improvement or transformation? A good parallel to this is work on climate change, where the City and State have set a goal of 25% emissions reductions by 2020 and 80% by 2050.

25% by 2020 is significant change, don’t get me wrong. And no one has figured out exactly how to get it. But it is about low-hanging fruit and doing what we already do more efficiently. By contrast, 80% by 2050 means transformation of our economy.

And so it is in education. If we set the system goals right, if we unleash the power of self-organizing, and if we are smart about other systems levers I haven’t even talked about – like improving information flows – then maybe, just maybe we can double the college completion rate in Boston so that three out of ten (instead of 1.5 in ten) high school freshman hit that benchmark.

Barr has its priority list of what needs to be done to get there.

But to my mind that is the 25% by 2020 goal. Not easy. But not enough.

The only way to get to the public education equivalent of 80% by 2050 will be complete shifts in our paradigms and recalibrating our goals.

Shifts that allow us to imagine a world where we no longer see middle class flight and segregated school systems as inevitable, where the structural inequity of affordable housing located far from good jobs and schools becomes only a memory.

Chris asked us to tell you how to make a bigger, better difference faster. Earlier I lied to you – I said that Donella Meadows most powerful lever was paradigm change – actually greater than paradigm change is the ability to become unattached to paradigms –– to stay flexible so that we can see the black swan.

So my mantra – is stay outraged by the pace of change – but curious about where the next paradigm shift is coming from – it may be from somewhere else in the globe or from someone in this room like Nick Donohue with mass customization of learning.

Thank you.

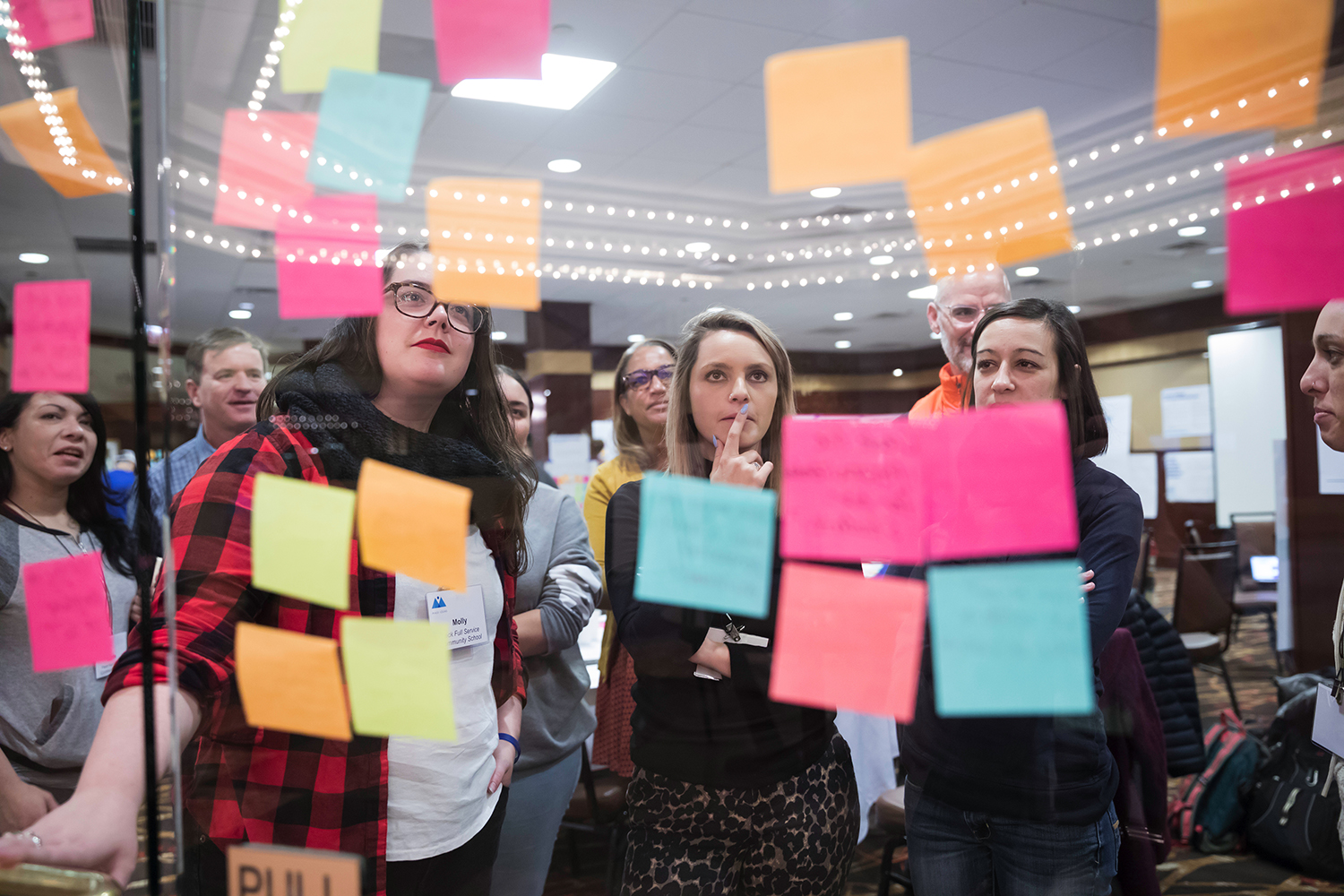

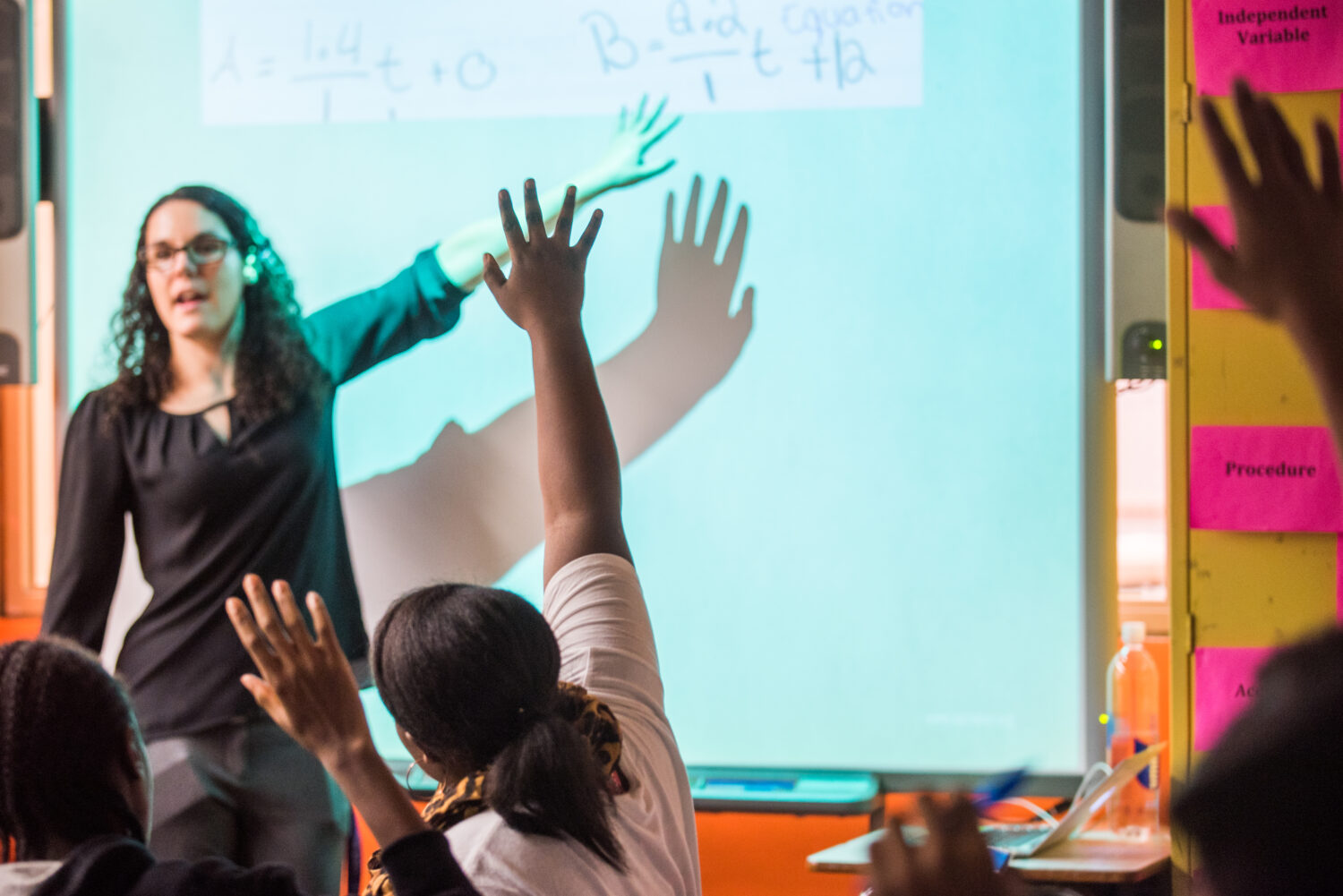

Photo by Lou Jones